Delivering social change with Elixir at Change.org

Welcome to our series of case studies about companies using Elixir in production. See all cases we have published so far.

Change.org is a social change platform, with over 400 million users worldwide. Two years ago, their engineering team faced a challenge to migrate their messaging system from an external vendor to an in-house solution, to reduce costs and gain flexibility.

This article will discuss how they approached this problem, why they chose Elixir, and how their system grew to deliver more than 1 billion emails per month. Change.org is also hiring Elixir engineers to join their team.

The path to Elixir

The first step for Change.org’s engineering team was to outline the requirements for their system. The system would receive millions of events, such as campaign updates, new petitions, and more, and it should send emails to all interested parties whenever appropriate. They were looking for an event-driven solution at its core, in which concurrency and fault-tolerance were strong requirements.

The next stage was to build proofs-of-concept in different programming languages. Not many companies can afford this step, but Change.org’s team knew the new system was vital to their business and wanted to be thorough in their analysis.

Around this time, John Mertens, Director of Engineering, was coming back from parental leave. He used this opportunity to catch up with different technologies whenever possible. That’s when he stumbled upon José Valim’s presentation at Lambda Days, which discussed two libraries in the Elixir ecosystem: GenStage and Flow.

They developed prototypes in four technologies: JRuby, Akka Streams, Node.js, and Elixir. The goal was to evaluate performance, developer experience, and community support for their specific use cases. Each technology had to process 100k messages as fast as possible. John was responsible for the Elixir implementation and put his newly acquired knowledge to use.

After two evaluation rounds, the team chose to go ahead with Elixir. Their team of 3 engineers had 18 months to replace the stack they had been using for the last several years with their own Elixir implementation.

Learning Elixir

When they started the project, none of the original team members had prior experience with Elixir. Only Justin Almeida, who joined when the project had been running by six months, had used Elixir before.

Luckily, the team felt supported by the different resources available in the community. John recalls: “We were in one of our early meetings discussing how to introduce Elixir into our stack when Pragmatic Programmers announced the Adopting Elixir book, which was extremely helpful in answering many of our questions.”

The new system

The team developed three Elixir applications to replace the external vendor. The first application processes all incoming events to decide whether an email should go out and to whom.

The next application is the one effectively responsible for dispatching the emails. For each message, it finds the appropriate template as well as the user locale and preferences. It then assembles the email and delivers it with the help of a Mail Transfer Agent (MTA).

The last application is responsible for analytics. It receives webhook calls from the MTA with batches of different events, which are processed and funneled into their data warehouse for later use.

After about four months, they put the new system in production. While Change.org has dozens of different email templates, the initial deployment handled a single and straight-forward case: password recovery.

Once the new system was in production, they continued to migrate different use cases to the system, increasing the numbers of handled events and delivered emails day after day. After one year, they had completed the migration ahead of schedule.

Handling spikes and load regulation

Today, those applications run on a relatively small number of nodes. The first two applications use 6 to 8 nodes, while the last one uses only two nodes.

John explains they are over-provisioned because spikes are relatively frequent in the system: “for large campaigns, a single event may fan out to thousands or hundreds of thousands of emails.”

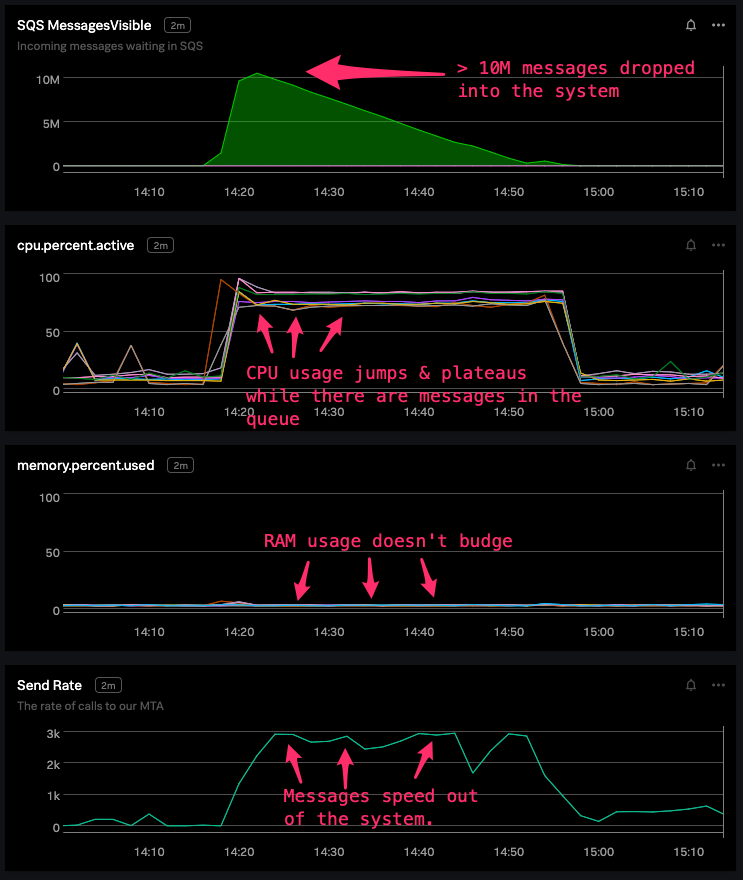

The team was kind enough to share some of their internal graphs. In the example below, you can see a spike of over 10 million messages coming to the system:

Once this burst happens, all nodes max their CPUs, emitting around 3000 emails per second until they drain the message queue. The whole time memory usage remains at 5%.

The back-pressure provided by the GenStage library played a crucial role in the system’s performance. Since those applications fetch events from message queues, process them, and submit them into third-party services, they must avoid overloading any part of the stack. GenStage addresses this by allowing the different components, called stages in the library terminology, to communicate how much data they can handle right now. For example, if sending messages to the MTA is slower than usual, the system will naturally get fewer events from the queue.

Another essential feature of the system is to work in batches. Receiving and sending data is more efficient and cost-effective if you can do it in groups instead of one-by-one. John has given a presentation at ElixirConf Europe sharing the lessons learned from their first trillion messages.

The activity on Change.org has grown considerably over the last year too. The systems have coped just fine. Justin remarks: “everything has been working so well that some of those services are not really on our minds.”

Working with the ecosystem

Change.org has relied on and contributed to the ecosystem whenever possible. During the migration, both old and new systems had to access many shared resources, such as HAML templates, Ruby’s I18N configuration files, and Sidekiq’s background queues. Fortunately, they were able to find compatible libraries in the Elixir ecosystem, respectively calliope, linguist, and exq.

Nowadays, some of those libraries have fallen out of flavor. For example, the community has chosen gettext for internationalization, as it is a more widely accepted format. For this reason, Change.org has stepped in and taken ownership of the linguist library.

As Change.org adopted Elixir, the ecosystem grew to better support their use cases too. One recent example is the Broadway library, which makes it easy to assemble data pipelines. John explains: “Broadway builds on top of GenStage, so it provides the load regulation, concurrency, and fault-tolerance that we need. It also provides batching and partitioning, which we originally had to build ourselves. For new projects, Broadway is our first choice for data ingestion and data processing.”

Elixir as the default stack

As projects migrate to Elixir, Elixir has informally become the default stack at Change.org for backend services. Today they have more than twenty projects. The engineering team has also converged on a common pattern for services in their event driven architecture, built with Broadway and Phoenix.

In a nutshell, they use Broadway to ingest, aggregate, and store events in the database. Then they use Phoenix to expose this data, either through APIs, as analytics or as tooling for their internal teams.

One recent example is Change.org’s Bandit service. The service provides a Phoenix API that decides which copy to present to users in various parts of their product. As users interact with these copies, data is fed into the system and analyzed in batches with Broadway. They use this feedback to optimize and make better choices in the future.

The team has also grown to ten Elixir developers thanks to the multiple training and communities of practice they have organized internally. Change.org is also looking for Elixir backend engineers, as they aim to bring experience and diversity to their group. Interested developers can learn more about these opportunities on their website.